May 27, 2020

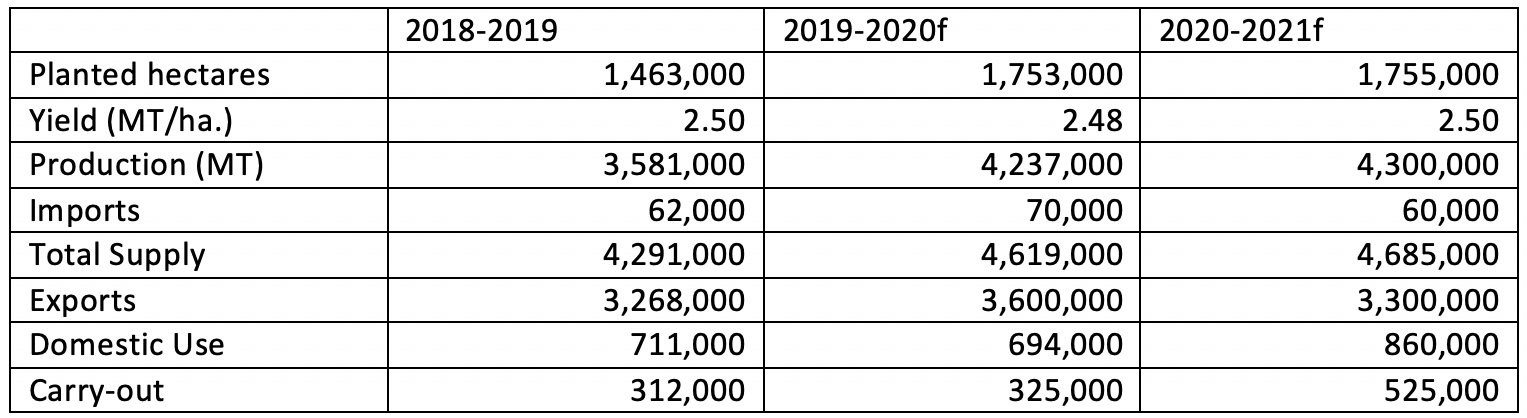

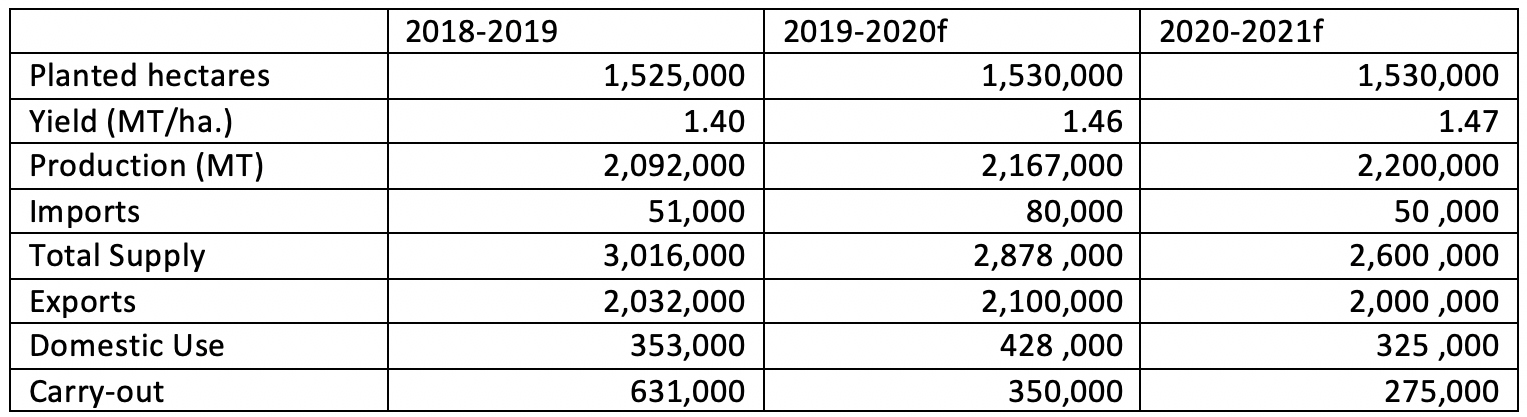

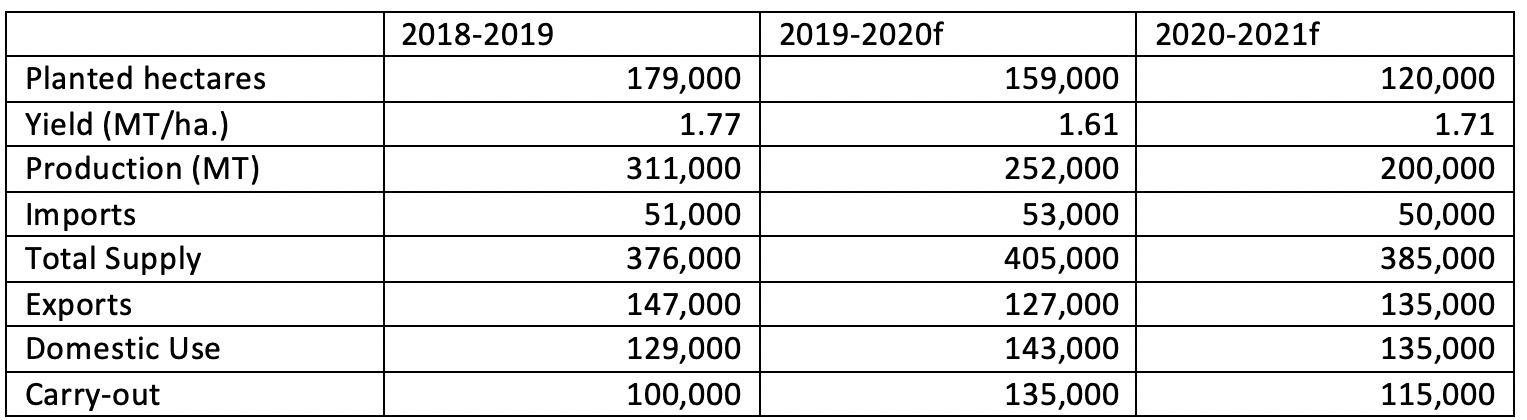

Area estimates and production projections for Canada and U.S. pea, lentil and chickpea crops.

A series of unusual springtime snowstorms hit Western Canada and the U.S. Northern Plains, two major pulse growing regions, just as planting season was getting underway. The cold, wet weather delayed the seeding of summer crops, but forecasts are promising fairer weather ahead and growers are moving aggressively to get their pea, lentil and chickpea crops in the ground.

To get a better sense of the situation on the ground, the GPC checked in with industry insiders in three major North American pulse growing regions.

Saskatchewan Pulse Growers Executive Director Carl Potts says the cold and wet conditions delayed the start of pulse crop planting by five to seven days. He notes, though, that Canadian growers are capable of seeding large areas rather quickly and, given that the weather conditions have improved, he expects pulse growers have made up for the slow start.

According to the latest Saskatchewan crop report, thanks to dry conditions during the week ending May 18, growers made good headway, more than doubling seeding progress to 51% and getting the pace on par with the five-year average. In terms of pulses, field pea, lentil and chickpea plantings stood at 82, 78 and 69% respectively. In neighboring Manitoba, the crop report for the week ending May 19 indicates the seeding of the pea crop is complete in the eastern and central parts of the province, and more than 50% planted elsewhere. In Alberta, the May 12 crop report indicates planting progress on dry peas, chickpea and lentils at 77, 89 and 88%, respectively.

“In Canada we always have weather events, so this is nothing extraordinary,” says Farhan Adam of Marina Commodities, based in Ontario. “If we finish planting by late May, we should be okay.”

Adam expects growers will eventually get all their intended pulse acres in the ground. The latest StatCan figures have the seeded area remaining flat for both peas and lentils. Both Adam and Potts agree with StatCan in terms of the dry pea area, but they take issue with the lentil seeding estimate.

“The StatCan numbers are based on a March grower survey,” explains Potts. “Prices have gotten stronger since then. Particularly on red lentils.”

Adam indicates that following the imposition of national lockdowns to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, grower prices on lentils jumped from 20 to 35 cents. The improved prices piqued grower interest and both Potts and Adam estimate lentil seedings are up 15% from last year.

“I expect a 10-15% increase in the red lentil area and production at 1.5 to 1.6 million MT,” says Adam. “I foresee a 15% increase in the green lentil area.”

On peas, Adam sees the breakdown as 3.6 million acres of yellow peas and 650-700,000 acres of green peas.

Chickpea plantings, on the other hand, are down significantly this year as markets continue to be weighed down with surplus production. StatCan estimates a 21% decrease in the chickpea area this year.

Although the feeling in the industry is that chickpea prices will improve toward the end of the year, growers in Canada were also worried about ascochyta blight. Last year, an outbreak of a new strain resulted in significant losses.

Source: StatCan, Outlook for Principal Field Crops, April 22, 2020.

Source: StatCan, Outlook for Principal Field Crops, April 22, 2020.

Source: StatCan, Outlook for Principal Field Crops, April 22, 2020.

The major pulse growing states in the U.S. Northern Plains are Montana and North Dakota. As in Canada, wet and cool weather conditions in the Northern Plains delayed the start of pulse planting this year. Brian Gion of the Northern Pulse Growers estimates the late start put pulse seeding back about a week.

According to the USDA’s Montana crop report, dry pea planting progress was at 79% as of May 17, ahead of last year’s 74% but behind the five-year average of 85%, with 35% crop emergence. Lentil crop planting progress was at 73%, behind the five-year average of 78%, with 25% crop emergence. In North Dakota, pulse seeding was farther behind, with dry pea planting progress at 49% as of May 17, compared to the average of 75% for that date.

In early May, Phil Hinrichs of Hinrichs Trading visited the pulse growing area in Montana and was greeted with a blizzard that dumped three inches of snow in the region. He heard that conditions in North Dakota were even more challenging and expects that production there won’t likely be much of a factor.

In mid-May, Gion says the region got hit with frost, but indicates that pulse crops had not emerged in the affected area and therefore were spared the consequences.

The USDA estimates a decrease in the nationwide seeded area for dry peas, lentils and chickpeas. For Gion, the USDA’s numbers sound about right for chickpeas given the surplus inventories and subsequently low prices.

“We are burdened with almost a year’s worth of carryover,” says Hinrichs. He believes the chickpea area this year will actually be even less than the USDA’s estimate. “I think we’ll have somewhere between 325-345,000 acres of chickpeas this year.”

But on peas and lentils, Gion feels the USDA may be a bit on the low side.

In the end, though, growers based their planting decisions on pricing, and with pulse prices low at the time of seeding, fewer acres were planted to pulses this year.

“For the past year and a half or so, pulses have been losing area to soybeans,” says Gion. “Then you have the issue of a late planting date. Late planted pulses are at risk of getting hit by high temperatures in the summer and having pods abort.”

Despite the challenging weather and the late start, though, Hinrichs indicates that growers’ did not waver from their pulse planting intentions. In fact, he reports that some additional chickpea acres went in the ground in early May.

“Some growers were on the fence about planting chickpeas, but as planting got more and more delayed, they decided to seed them,” he says. Chickpeas tolerate heat better than peas and lentils, and are the least risky of the three, he explains.

The Pacific Northwest region of the U.S. includes the important pea and chickpea growing states of Washington and Idaho. Here, weather conditions were more favorable than in Canada and the Northern Plains. In fact, Hinrichs describes the conditions as exceptionally good and reports that the chickpea crop was seeded between April 20-30, the prime planting window, with the pea crop at 75% seeded by the end of April.

The USDA reports that in Idaho, dry pea planting progress was at 85% as of May 17, ahead of the five-year average of 80%, with 73% crop emergence. In southern Idaho, however, Hinrichs visited fields at 3,500 to 4,000 feet above sea level, where planting was just getting started, and indicates the temperatures were very cold and there were frost issues.

Hinrichs Trading is a major U.S. kabuli chickpea supplier. Asked if the spike in pulse consumption following the COVID-19 lockdowns helped reduce the surplus carryover, Hinrichs says any gains in consumer demand are wiped out by losses in the food service sector.

“The carryover was being consumed at a nice pace by canners, packagers and hummus makers, but then the pandemic took people out of plants,” says Hinrichs. “They could lose more than 50% of their production just trying to wade through the essential business plan they have to live by. So we’ve seen our food service demand die off by almost 40%. We hope to see it come back, but we’ve already lost two months and it will take another two to get it back to 50%. By then we’ll have new crop.”

Canada / USA / Western Canada / U.S. Northern Plains / U.S. Pacific Northwest / Farhan Adam / Carl Potts / Brian Gion / Phil Hinrichs

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.