December 24, 2019

Snow and rain made for a messy harvest in the major dry bean growing regions.

Grafton, North Dakota, October 23, 2019. Photo courtesy of Sam Peck.

From Western Canada to the Northern Plains and Midwest region of the U.S., the weather pattern was basically the same this harvest season: wet and cold. These conditions caused major harvest delays and impacted the quality of the dry bean crop. In many instances, the delays were so prolonged and the quality of the crop so deteriorated that the beans were left abandoned in the fields.

“It seems we skipped the fall season and went straight from summer to winter this year,” says Keven Sawchuk of Viterra, reporting from the Canadian Province of Alberta. “In Western Canada we had our first major snowstorm early on, in late September. That storm dumped as much as two feet of snow in parts of the western prairies.”

In the U.S., major snowstorms also impacted bean crops in Michigan, across the Great Plains and into the Rocky Mountain region.

“It’s been one long, agonizing bean harvest,” summarizes Judd Keller of the Kelley Bean Company. “I’ve never seen anything like it. And in Mexico, with the drought there, they got half a bean crop, too. The whole Northern Hemisphere has had a really bad bean crop this year.”

In Mexico, the spring-summer bean crop is estimated at around 400,000 MT, down 52% from the previous spring-summer season. In the U.S., the USDA’s December 10 Crop Production report lists the 2019 dry bean crop at 1,079,550 MT (23.8 million cwt), down nearly 4% from last year. According to StatCan’s online database (accessed December 16), Canada’s dry bean harvest amounted to 316,800 MT, down 7% from last year and a far cry from earlier expectations of 350-360,000 MT. This year, Canadian growers seeded an unusually large area to dry beans (160,000 ha.) because of the tariffs and quotas affecting lentil, chickpea and pea exports into major markets like China and India,

Below, we take a closer look at the on-the-ground situation in key growing areas in both Canada and the U.S.

Michigan, a major dry bean growing state, produces a variety of commercial classes, but its top three are black, navy and small red beans. Black beans alone typically account for more than half of Michigan’s dry bean output.

This year, the bean crop there was planted late due to wet conditions, and then harvested late due to snow. Joe Cramer of the Michigan Bean Commission estimates 5% of the crop may have been left unharvested and overall production may be down 15-20% from the 170,000 MT the Commission projected back in July.

“Almost everything will need drying, which is very unusual,” he says. “Quality, though, actually held up quite well, except for the part of the crop that was harvested very late. Late-harvested pintos did have discoloring.”

In Minnesota, an important kidney-bean growing state, the season started out cool and wet, resulting in planting delays. Although conditions improved during the summer, the cool wet weather returned just as the crop was ready for combining, creating further delays and pushing the end of the harvest back a full month.

“With the cool, wet weather, we had more white mold issues than normal,” says Mark Dombeck, a Minnesota bean grower. “On the bright side, if it had been warmer, we would have had sprouting, too.”

Dombeck reports below average yields on kidney beans but good quality despite the challenging weather conditions. The navy bean crop was harvested before the weather turned ugly and ended up with average quality and yields. The black bean crop was harvested late, but nonetheless ended up with average yields and normal quality. For pinto beans, however, it’s another story.

“On pintos, we have some good quality, a lot of fair quality and some poor quality,” assesses Dombeck. “Because of the late wet conditions, the yields were below average.”

Bean field in Minnesota. Photo courtesy of Mark Dombeck.

Across the border in North Dakota, Webster-based bean grower Kevin Regan reports similar woes with pinto beans. North Dakota is the top dry bean producing state in the U.S. and pinto beans typically account for a little less than half of its dry bean output.

“It’s been a real challenge in our area,” says Regan. “We had a blizzard October 11th that dumped two feet of snow. Even after the snow melted, conditions remained very wet and very cool.”

Regan was only able to get half his pinto bean crop off before more snow hit the area. Of the half he did harvest, he says 50% of the pods were crushed flat to the ground.

North Dakota bean field. Photo courtesy of Kevin Regan.

The seven-state Rocky Mountain region contributes significant volumes of pinto, great northern and, to a lesser extent, light red kidney beans. Judd Keller of the Kelley Bean Company reports that for the most part Rocky Mountain bean growers had to contend with the same weather issues as the other major bean growing areas.

“We had delayed planting with wet, cold weather,” he says, summarizing the growing season. “Then during the summer, we had more hailstorms than usual, and the hail damage was atypically severe.”

On top of that, in Nebraska, where 80% of the U.S. great northern bean crop is produced, an irrigation tunnel collapsed and left an estimated 15,000 acres of dry bean crops without a reliable source of water. By Keller’s estimation, between the hail damage and the loss of irrigation, production ended up 25-30% below initial expectations.

“I think a lot of us are maybe using 1,900 to 2,000 pounds per acre in our calculations,” says Keller of the region as a whole. “A good yield nowadays is 2,400 to 2,500 pounds/acre. So yields are down. And the quality was affected, too.”

In the case of pintos, the early-harvested beans escaped the effects of the rain. But because much of the pinto crop had been pre-sold, only discolored stocks remain available.

On great northerns, Keller suspects a good part of what was harvested will end up discarded by electric eyes due to wrinkling and yellowing. Back in July, the expectation was for a great northern crop of about 54,400 MT, but Keller believes commercially viable production will end up being a third smaller, at 36,300 MT.

Navy beans account for about a third of Canada’s dry bean production. The other major bean classes grown there include pinto, black and great northern beans.

This autumn, bean growers in Western Canada could do little more than watch crop losses and quality issues pile up as the major September 27th snowstorm was followed by intermittent rain and snow throughout October. Farther east, in the provinces of Manitoba and Ontario, where dry beans are also produced, the situation was much the same.

Keven Sawchuk of Viterra estimates Ontario bean growers were able to harvest about 90-95% of their bean crops. In Manitoba, he expects 15% of the beans went unharvested, while in Western Canada, 5-7% of the bean crop was left in the fields.

In terms of yields, Sawchuk anticipates they will be slightly below the five-year average in Western Canada and Ontario, but significantly lower in Manitoba, where more beans were left unharvested and there were greater losses due to excess moisture.

With respect to quality, Sawchuk says, “The cleanout of this crop will be a significant issue. There’s going to be a high percentage of wrinkling for North American white beans.”

On black beans, Sawchuk estimates 15% of the crop went unharvested in Western Canada due to wet conditions and frost damage. He expects there were losses in Manitoba and Ontario as well, given the late planting due to wet weather combined with the early onset of winter. However, due to disappointment with pinto bean prices in recent years, the area seeded to black beans has been trending upward in Canada. Consequently, despite the crop losses, the black bean crop may end up being the same size as last year’s.

Across North America, the expectation is that, with production down and not much in the way of carry-in, dry bean supplies will fall short of demand in 2019/20.

“We are in a bull market,” Sawchuk sums up. “The North American dry bean supply is tight across all types. Pinto beans are incredibly tight right now and the market is rising. We thought we might have been heavy with cranberry beans this campaign, but not now that pinto prices are escalating.”

The white bean trade is also tight. Sawchuk expects navy and great northern bean carryout to be in single digits. Canada’s white bean trade into Europe has benefitted from EU tariffs on U.S. beans, a retaliatory measure imposed after the U.S. slapped tariffs on EU aluminum and steel.

“Because of the short supply on pintos and whites, we are starting to see some substitution effects,” says Sawchuk. “That’s creating opportunities for small reds, pinks, black and even kidney types. We are seeing this in the U.S. canning market, and I suspect in the Caribbean we’ll see markets like the Dominican Republic, which usually takes pintos, opting for more economically priced black and cranberry beans instead.”

Over in the U.S., Keller is of the same opinion on pintos. He believes North American pinto bean inventories could clear out by late summer. That is, if growers are willing to sell.

“If we go with the idea of a 7 million cwt crop and assume another 2 million cwt in carryover, we maybe have a 9 million cwt supply of pinto beans,” figures Keller. “And the word is that demand is 11 million cwt. So seeing this, the growers aren’t selling. I mean, they are really hurting this year, because its not just the bean crop that was bad this year, its everything else, too. Growers are looking to maximize whatever they managed to harvest this year.”

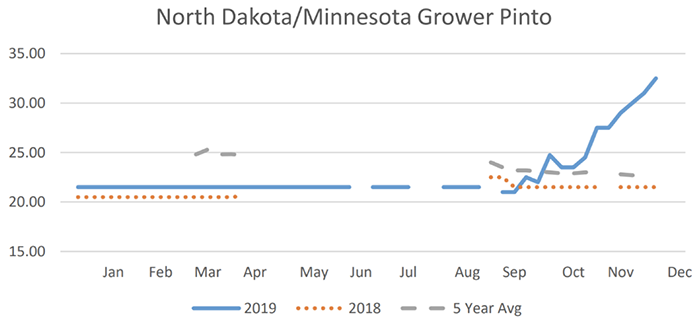

Source: USDA Bean Market News, for the week ending December 17, North Dakota/Minnesota grower prices for pinto beans.

Furthermore, Keller points out, pinto beans are hard to replace. “They are really only grown in significant volumes in the three countries of North America. So in a year like this one, with production problems at all three origins, you don’t really have anywhere else to import from.”

On white beans, Keller expects total U.S. great northern production to amount to 36-37,000 MT, which is well short of the 60,900 MT that are normally sold over the course of a year.

With respect to black beans, China has been fading away as a supplier, leaving the nations of the Americas as the only providers. With a poor harvest this year, Mexico is sure to be in the market for black beans in 2019/20.

Traditionally, Michigan is one of Mexico’s key black bean suppliers. Before the weather woes, growers there were looking forward to a large crop and a windfall given Mexico’s short crop. The opportunity is still there, says Cramer, but with this year’s limited production, Michigan’s bean growers won’t be able to fully capitalize on it.

Canada / USA / Keven Sawchuk / Judd Keller / black beans / navy beans / small red beans / pinto beans / Mark Dombeck / Kevin Regan / Joe Cramer

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.