October 7, 2021

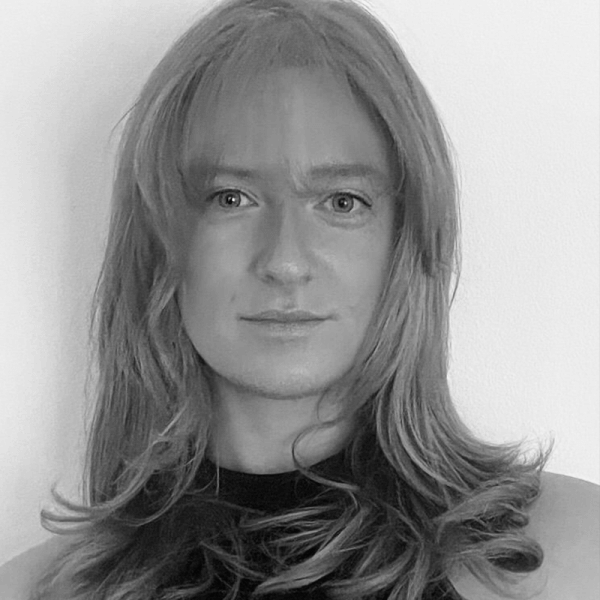

Led by members of the Science and Engineering faculties at the University of Sydney, the Transitioning Australian Pulses into Protein-based Food Industries project will work on the development of Australian pulses into plant protein ingredients and products and was recently awarded $993,573 under the Global Innovation Linkages Program. It is a 3 year project with support and partnership from AEGIC, Roquette, Clextral, All G Foods and Wide Open Agriculture. Originally from Canada, Professor Brent Kaiser of the University of Sydney has a background in plant genetics and is the project lead. We caught up with him to discuss what the new initiative means for the Australian pulse industry.

Getting more pulses in rotation is key and getting growers accustomed to growing them as well, because they’ve had a lot of bad experiences. Australia inherited pulses from the European colonisation and we’ve only been growing them for about 45 years. They’ve taken a long time to establish themselves as a significant rotational crop and they’re often 3rd or 4th choice; canola and wheat are big competitors. The climate is warm and dry and the soil is quite impoverished and pulses tend to suffer easily from disease. Farmers have a long memory; if things don’t grow, it may take 20 years for them to grow that crop again. But the demand is there and growers are business people: they respond to the dollar. In Australia we grow about 3 million tons of pulses and export probably 90% of it overseas. It’s not a main staple on the plate like in Europe but we’re hoping that this plant-based movement will help to change the industry into one that’s restructured towards value-added opportunity for growers. We have an industry in Australia that’s poised to participate but it’s very traditional and conservative. It takes time to create the mechanism and we’re about 5 years behind more modernised pulse-growing countries.

It’s a combination of several things. I come to pulses knowing already that they’re good for the environment, for farming systems and for consumers. Australian pulses have high values on international markets but we’re also looking to have a more environmentally sustainable footprint. What catalyzed a lot of this activity was the fact that we’ve been going through a time when the pulses we grow are extremely popular and highly valued. At the same time, this huge global trend towards the plant-based protein started to take hold and that allowed us to observe what was happening in competing countries. So the question was: how do we transition from being dependant on global markets to basically becoming a driver of what we do? Because we're running a risk: Australia produces about 6% of the world’s pulses but we’re focused on a few pulses that are in high demand: chickpeas and lentils. There’s a very aggressive market for those crops and we were slowly becoming a smaller player on the global market, a price taker not a setter. The tarifs set the tone for that and we lost market responsiveness. The goal is to build our own plant protein industry in Australia and make it sustainable enough to feed into the markets that are ours to participate in, particularly South East Asia. However, it requires a whole new secondary industry to be built from scratch because although we have companies that build plant protein-based foods here in Australia, they import all their protein from Canada, the US and China. At the same time, we’re growing 3 million tons of grain that gets sold for $500 a ton but if it was a protein ingredient, it would sell for much more.

We have to work with what we’ve got. We have effectively six major pulses that we grow and each one is a different beast in the context of extracting protein. One of our major products is desi chickpeas, which are full of tannins, so one challenge is how do you convert a crop like that into something suitable for fractionation? All the low-hanging fruit has already been developed with yellow peas and soybeans so now it’s hard to get a company that has an existing program or recipe to readjust to chickpea or lentil or green pea. As an industry, we need to define what are the types of pulses that work well for the plant protein industry and then adjust our production but also adjust the manufacturing processing to give the flavour profile and texture that consumers want. So it's been eye-opening because we thought we could just grind anything up and sell it as protein but, unfortunately, we can’t! Your sensory paletes will quickly tell you if something doesn’t taste good and so the risk is we have 2 million tons of chickpeas and no plan for what to do with them.

Exactly! Our pulses have done so well in India because they go right into the domestic food market and onto the plate. Our mission right now is to develop the methods that we need that suit the Australian conditions and get high quality protein isolates to the food manufacturing companies that will be willing to pay for them against low-price soybeans coming from China and the US. We need to provide a high quality protein source and make it so different and so exquisite that customers will keep buying it. Our program is to begin that process and compliment other research activities in Australia. We have 2 other very large programs that are under review: one is a 10-year R&D program to firmly establish the whole plant protein industry in Australia, kind of like what the Canadians did 5 years ago with PIC, where you bring in industry, the government and universities to create a large pool of money to do R&D and get things up and running. And then, more recently, we’ve been able to get investment from companies around the world to start building the key infrastructure like the processing plants etc. One of our partners is Roquette and another is Clextral, which builds the texturization tools for proteins.

We’re hoping to triple production in Australia on the same acreage. We haven’t invested too much in research compared to France or Canada to improve productivity, harvest etc, but we think that money will drive acreage. We saw that happen in 2016/17 when pulse prices were really high and chickpeas and lentils were going for $1500 a ton; those areas that were big wheat-producing areas became chickpea producers overnight.

We’ve been working on that. Since we first imported pulses into Australia in the 70s, there’s been an ongoing improvement program to diversify the germplasm and select more drought- or heat- tolerant varieties. We’re also looking at alternative pulses like pigeon pea, which is perfect for the Australian climate but it’s not great for fractionation. The pulses we grow now are designed to go straight onto the plate. It’s kind of like wine, we’re effectively growing grapes for wine. It’s a different context for the new market. Until now, there hasn’t been that much interest in where the crop will go after it leaves the farm gate but now you have to follow that crop through the whole supply chain. Now it needs to meet the criteria of the sensory panels that test the taste of the new products. That’s what you have to start engineering for in a breeding context: how to get a certain type of protein in the seed or less tannins or more iron or key amino acids that are currently missing. Now we’re not growing a grain crop that’s going to go into a container and get shipped off, we’re growing a very fine food so we need an overhaul.

I think that where plant proteins will start to take their form is in the broad ingredient market. If you look for where the protein comes from in a food product, it’s currently mostly animal or dairy-based. In the future, I think we’ll see a lot more diversity regarding which protein goes into a product like a soup or a sauce and 30/40% of your daily protein intake will be plant-based, hopefully pulse based. We’ve done some gap analysis and if you look at where the largest populations sit, there’s a deficiency in available protein. There are growing middle classes that are often demanding red meat as their first choice protein source. Every source will be challenged to meet the demand and then when you throw in the environmental issues and more pressure on carbon neutrality, it’s going to be even harder to deliver that protein. Even if you design your own fermenting system to make proteins out of yeast, fungus or cells, all the inputs have to come from somewhere. All that nitrogen and carbon comes from agriculture and I’m happy that the plant-based meat industry has taken on this challenge. If you look at McDonalds, for example, if they sell 5% of their hamburgers as plant-based, that makes a difference.

There are different pockets across the country; it’s a growing area. It’s exciting for producers too. One of the things we want to do in Australia is create a regionalization drive, so if you want to buy a lentil-based protein, you go to a certain region of the country that is known for producing high quality lentils and that is tracked from the paddock to the fork, kind of like the way you buy wine because of the terroir. In Australia, we have such a large landmass and there are areas that are known for certain products; it’s just a matter of how you capture that identity, and market it. That’s another way to diversify and build upon what’s happened fortuitously from just growing a good crop regionally. More industries want to have total control over what they source, where it comes from and how they can sell it. It creates jobs and industries and capabilities; it starts a wave. We hope we can catch up to the Canadians and the Europeans and the Americans. There’s a lot of money floating around, waiting for opportunity.

I think that’s a modest number. It’s displacing an existing industry; you’re revolutionising a farm into a much more sustainable production system that in the long term provides better outputs for the country and the people. When protein demand really starts to take place, you can see large meat companies buying plant-based companies because they’ve realised they don't sell meat, they sell protein. It doesn’t matter what form it’s in, once it’s in your gut it’s all the same, so there’s a lot of interest from traditional industries moving into these new industries.

We’ll definitely spend some time on faba beans because their flavour is probably the blandest and, from a simple extraction process, it’s probably the easiest to do compared to chickpea or lentil, where you have a lot more tannins and astringent flavours in the seed coat, which also get extracted when you extract the protein. We’ll also use chickpeas, because they’re interesting and have a high fatty acid component, which is useful for flavours. What we’re finding with pulse proteins is that when you try to extract the protein, you strip everything out, but your mouth really wants that lipid fraction to give your taste receptors a profile that’s compatible with the food you’re eating. There are natural fatty acids to enhance in chickpeas, either through genetics or selecting different types of germplasm.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.