August 29, 2019

A month ahead of planting, experts weigh in on what to expect from Mexico’s chickpea crop.

Two years ago, kabuli chickpea prices were at all-time highs. In Mexico, exports went for as high as US$ 2,400/MT C&F. The sky seemed the limit and growers at all origins eagerly expanded the planted area, hoping for a piece of the action. Instead, the resulting surplus production caused a worldwide glut and caused the market to crash. Since then, Mexican chickpea export prices have been below US$ 935/MT C&F.

“That means selling at a loss for most of the big players in Mexico,” says Felipe Sandoval of BeGrait Beans & Grains.

Given the prevailing downward price trend, movement out of Mexico has slowed as of late. Buyers are cautious and sellers are rejecting bids at current levels.

Throughout the world, kabuli chickpea traders are on the lookout for signs of a market reversal. At the moment, all eyes are on Mexico, which begins to plant the next significant kabuli chickpea crop in October.

Mexico’s kabuli chickpea crop is grown mostly in the northwestern states of Sinaloa and Sonora. Planting typically starts in mid-October in Sinaloa and wraps up in late December in Sonora. Although it is still more than a month away, it is already clear that there will be a significant reduction in the area seeded to kabuli chickpeas this fall. The question is just how big of a reduction will it be.

Mexico’s crop year runs from March, when new crop is harvested, through February. The crop that will be planted this autumn and harvested in March of next year, therefore, is the 2020 crop.

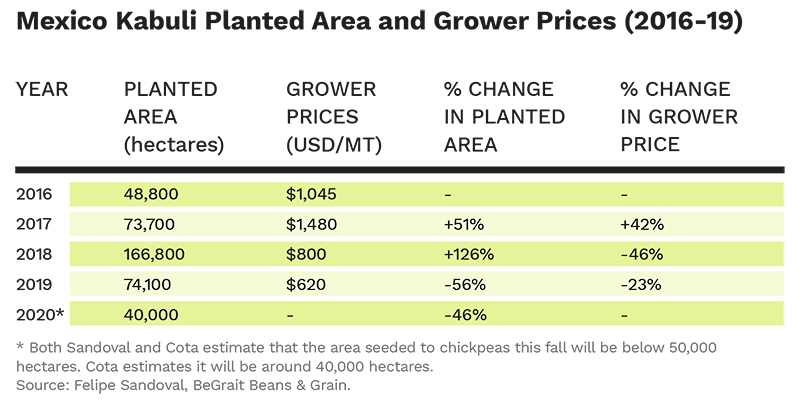

Plantings already fell by 56% from 166,800 hectares for crop year 2018 to 74,100 hectares for crop year 2019. For crop year 2020, Eleazar Cota of Alazan says the outlook for kabuli chickpea plantings has worsened since he sat on the Pulses 2019 kabuli chickpea panel back in June.

According to both Cota and Sandoval, several factors are likely to push growers to plant a crop other than kabuli chickpeas this coming cycle. The first and most influential of these factors is price. According to Cota, the gap between grower prices for kabuli chickpeas versus other alternatives has grown since Pulses 2019. Presently, kabuli chickpea prices to the grower are as low as 10 MXN/kg. Both corn and beans have more attractive pricing. In the case of mayocoba beans, Cota says grower prices are at 27 MXN/kg. Beans have become especially attractive to Sinaloa and Sonora growers following the poor summer/spring planting season in the major bean-producing states of Zacatecas, Durango and Chihuahua, all of which saw crop sowing curtailed by severe drought conditions. The U.S. Dry Bean Council estimates Mexico seeded 42% fewer beans this spring/summer season.

Another factor is President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s push for food self-sufficiency. Both corn and beans are food staples in Mexico and their production is subsidized under the new government’s agricultural policies. Kabuli chickpeas, on the other hand, are predominantly grown for export, and therefore are unsubsidized.

And lastly, the climate conditions in Sinaloa and Sonora heading into the fall/winter planting season are ideal for seeding corn and beans, Cota indicates.

Based on these factors, he believes the kabuli chickpea seeded area could end up at around 40,000 hectares.

“That would be the lowest planted area in the past 15 years,” says Sandoval.

Like all other major kabuli chickpea origins, Mexico entered crop year 2019 with burdensome carry-in stocks, estimated at 98,000 MT. But both Cota and Sandoval point out that less than half of those inventories were comprised of Mexico’s renowned large-sized kabuli chickpeas (11 mm and larger).

“The market differentiates between the larger and smaller caliber sizes,” says Cota.

Most of the surplus inventories weighing down international prices are of smaller caliber kabuli chickpeas from major origins such as the U.S., Canada, Russia, Argentina and newcomer Türkiye (Türkiye had been a net importer until last year). Cota as well as Sandoval, therefore, anticipate good movement and improved prices for Mexico’s larger-sized product.

Cota estimates the 2019 carry-out at 20,000 MT. That should help restore balance to Mexico’s kabuli chickpea market, which has a tendency to experience wild price swings every two to three years.

“By the end of crop year 2020, with a very small crop because of the reduced area, I expect we’ll see inventories clear out and we won’t have much carry-out,” says Cota. In fact, he expects 2020 exports to fall to their lowest level in five years on limited supplies.

“The ideal,” says Cota, “would be to not have these peaks and valleys. The price that would be at equilibrium for growers and consumers would be US$ 1,100 to 1,200/MT.”

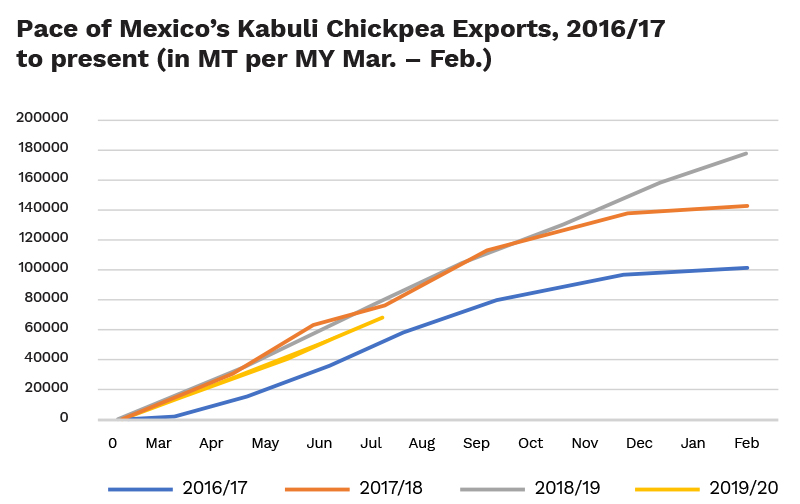

In the recent past, Mexico’s top kabuli chickpea export markets have been Algeria, Spain and Türkiye, not necessarily in that order. Thus far in crop year 2019 (March through July, 2019), Mexico exported 67,599 MT of kabuli chickpeas, behind last MY’s pace of 80,519 (March through July, 2018). So far this MY, Türkiye is the top destination, accounting for 21% of all kabuli chickpea exports. Algeria (15%) and Spain (14%) follow.

Source: Graph based on numbers provided by Bodega de Granos El Alazan

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.