September 19, 2024

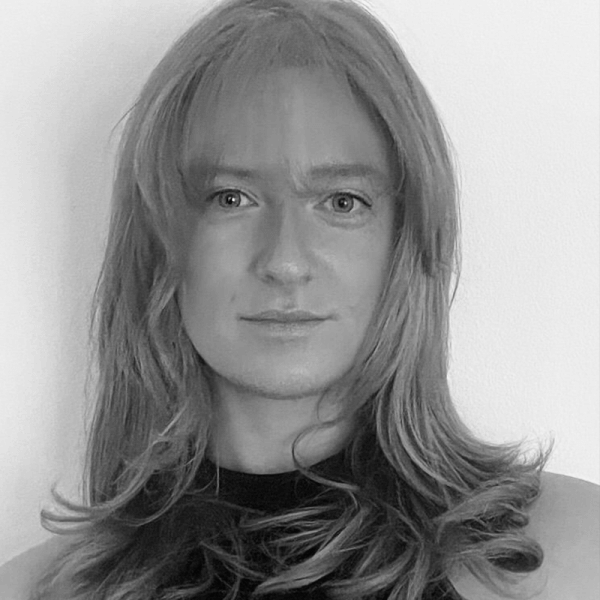

Dugald Reid is a group leader in the Department of Animal, Plant and Soil Sciences at La Trobe University, Melbourne. He speaks to Lara Gilmour about a recent breakthrough in his work on nitrogen fixation.

A genetic “off switch” that shuts down the process in which legume plants convert atmospheric nitrogen into nutrients was identified for the first time by a team of international scientists, led by La Trobe University researchers. The identification of the gene, says Ried, is an important breakthrough that can allow scientists to increase the biological ability of legumes to fix nitrogen and help increase crop growth and yield while also reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

pulses / legumes / nitrogen fixation / nitrogen / Dugald Ried / La Trobe University / Bill Gates / Gates AgOne / sustainability / future food systems

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.