May 10, 2023

The CEO of Bombi's Group, talks to Aniqah Majid about model farms, political and economic restraints and Pakistan’s unique pulses market.

Faisal Anis Majeed is the CEO of Bombi’s Group, a third-generation family business working in pulses for over 35 years. He is also involved in the Karachi Chamber of Commerce, the Rice Exporters Association of Pakistan and the Federation of Pakistan Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Faisal is one of the founding members of the GPC Young Professionals.

Faisal is speaking on the Pigeon Peas and Black Matpe panel at Pulses 23. Not registered yet? Sign up today!

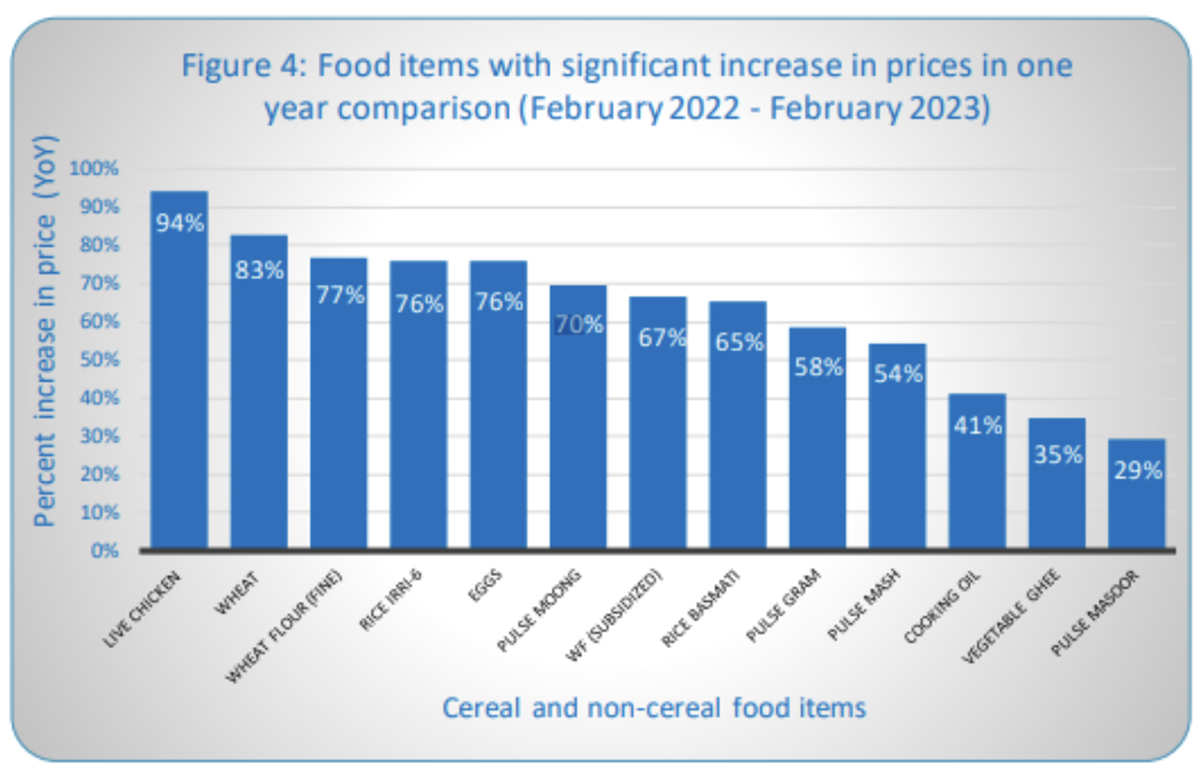

The price of pulses in Pakistan has increased in 2023 due to inflation. In January, more than 6,000 containers of pulses were kept at ports for two months due to the dollar shortage and the bank's reluctance to approve import documents, according to The Siasat Daily. The wholesale price of chickpeas had risen to 205 PKR per kg from 180 PKR on 1 January and inflation increased further into February and March, according to a recent World Food Programme report.

As an important consumer of pulses, ensuring global trade flows freely is significant for Pakistan. Faisal explains the intricacies of the market and what’s being done to encourage production and trade.

Faisal giving a presentation at the GPC executive committee in Cologne, Germany.

Pakistan's pulse market is unique because Pakistan is the only major buyer right now for pulses. Two major producers, Canada and Australia, are around 50% dependent on demand from Pakistan. India led this before. India is three times the capacity of Pakistan in terms of population and consumption of pulses. In the last three or four years, India has not been buying and is not active in the market, and whenever they want to buy, it's in small chunks and bulk vessels.

Pakistan imports around 1.5 million tonnes of pulses annually, and our local growth is only about 300,000. In 2010, we had a bumper crop of one million tonnes in Pakistan of desi chickpeas, but Pakistan has banned exports of pulses since 2006. This was because our demand was much more than our supply and local production, so the government banned all exports. In 2010, my dad Anis Majeed Bumbia, who was chairman of the Karachi Wholesales Grocers Association (KWGA), tried to start up the exports of pulses but the government was not supportive, which resulted in farmers losing money.

The market crashed badly, from 180 rupees per kg to about 80 rupees per kg. It was a massive crash, and many people defaulted in their local markets in Pakistan because of this. If exports were allowed, Pakistan would have been in a better position because, at that time, India was buying, and we could have exported to India or other markets, plus farmers and traders would have made a good amount of money.

With that, year-on-year, all local production has been diminishing, especially with desi chickpeas, because that was a significant problem we had.

1.6 million tonnes were cultivated in desi chickpeas; now, it's only 800,000 acres. In this area, the acreage is used for alternative crops, like oil seeds, making much better returns. This year for desi chickpeas, we estimate about 275,000 to 300,000 tonnes if all goes well.

Market Monitor Report March 2023 [Credit: World Food Programme].

They're doing a great job. In the last four years since they've stopped importing, they have encouraged their farmers to grow more, which has worked well for them.

I started working for the Rice Exporters Association in 2018. Many big exporters went into vertical integration, ready to import seeds, buy land and do lead agreements, do the farming themselves and then repurchase it. They got all the input for the farms, monitoring the crop and handling the cargo. Then they began exporting and earned a good fortune. It was difficult for the first two years, and they made losses, but they started making profits in the third and fourth years. We're trying to do the same thing in pulses.

But with pulses, the Government of Pakistan is not very supportive, and they don't have a minimum support price nor a mechanism to subsidise or incentives farmers to grow more. We are trying to convince the government that this is a value barrier. They have started a model farming project, which my brother, Bilal Majeed Bumbia, has visited. It was a small portion in which the yields were pretty good. If more farmers replicate this technology, we can improve our yields and plant in a much bigger area.

Credit: Faisal Anis Majeed

Pakistan consumes different varieties; one of the major ones is desi chickpeas. We consume around 650 to 700,000 tonnes annually, making up about 50% of our pulses. That's why there is a focus on improving the yield and growth of this crop.

We have smaller crops of red lentils and green moong beans. Last year, we had a very good crop of green moong beans, and we did not import a single container of them as our prices were good.

Time and again, whenever government and farmers focus on one crop, they can improve the yields and focus on more. With green moong beans, we experimented and got good yields, and we did not have to import from Brazil or Argentina. We are hoping that we can replicate the same with lentils.

Currently, Pakistan and India have a ban on trade. Four years back, we had trade relationships, and we used to import a lot of white camellia chickpeas. It was very helpful because, in four days, the supply would be in Pakistan. One-day loading, two days shipping period, four days on the port in Karachi. So it was quick trade and a very good trade.

We used to sell off potatoes as well - whatever excess crops we had in Pakistan, we used to export to India, and India would export pulses to Pakistan. It saved many freight, transit, energy, and planning costs. If the prices went up for one commodity, there would be a demand there, and quickly, you could manage it.

Cross-border trade is very important not only for Pakistan but for India as well. Pakistan imports a lot of desi chickpeas, and we rely mainly on Australia for that; other origins are Ethiopia and Uganda, but in limited quantities. So the major trade is still with Australia, and we have to plan accordingly and work on the target period and plans.

We wait around 40 to 60 days to receive the goods. There are positives and negatives, but Australia has been a reliable supplier and partner.

The same goes for Canada, which has been a very reliable source of chickpeas. And the US has been a good source of coverage for nine varieties. So Pakistan, in return, has been the most reliable country for exporters releasing cargo and making payments, even if they were making a loss. It's been a privilege in Pakistan that the default ratio is much less than the other countries.

We've been working with the local government; my association has been trying to convince them to invest more in pulses. We continue to work towards it. We are also trying to convince important people to look towards the farmer. The good side to this is that people are sitting in power who own cultivatable land. We are looking to advise them on how they can increase their yields and increase output and profits.

Hopefully, this will sound the alarm, and people will start growing pulses on their own, understanding the yields they're getting and the technology they need to grow them.

I was one of the five founding members and we've been working with the development of leadership and getting young people into the business and supporting new brands when they face problems while exporting or importing or if they need connections across the globe.

We have a Whatsapp group as well, so they can connect. Plus, we have social events at many pulses conferences, and it's an excellent opportunity to meet directly with people involved in different parts of the world dealing with pulses.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.