Last May, the Western Producer, a leading source of agricultural news from Western Canada, declared Kazakhstan the Saskatchewan of Asia. From the perspective of the global pulse industry, that’s no small thing. Saskatchewan is the top pulse-producing province in the world’s number one pulse-exporting country. United Nations Comtrade data shows that Canada’s pulse exports far exceed that of other origins. In 2018, for instance, Canada exported nearly 4.36 million MT of pulses, almost four times the volume exported by its closest competitor, Russia, with 1.13 million MT.

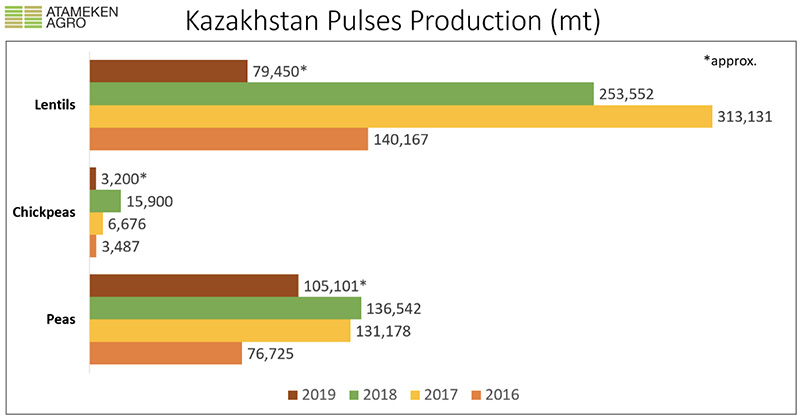

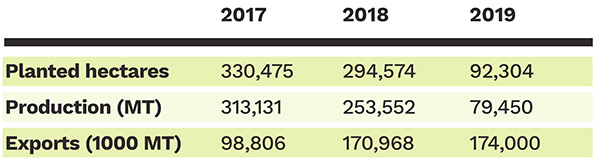

Although Kazakhstan remains far from Canada’s level, it nonetheless caught the attention of the global pulse trade when its pulse production suddenly exploded on the scene in 2017. The biggest increase was in lentil production, which hit a record 313,131 MT that year, up from 140,167 MT the previous year. That’s all the more remarkable when one considers that the lentil area expanded from a mere 70,000 hectares in 2014 to more than 330,000 hectares in 2017.

That same year, Kazakhstan also saw notable, albeit more modest, increases in pea production (from 76,725 the year before to 131,178 MT), and chickpea production (from 3,487 to 6,676 MT).

But now, less than a year since the Western Producer’s headline, Kazakhstan has faded from the global pulse trade as quickly as it appeared on the scene. According to Kintal Islamov, Chairman of JSC Atameken-Agro, the country’s 2019 red lentil production fell to 79,450 MT from 253,552 MT the year before.

The GPC first met Kintal at the Future of Pulses conference hosted by the Community of Pulse Producers and Customers of Ukraine, where he delivered an impressive presentation on the outlook for Kazakhstan’s pea and lentil crops. In this interview, he provides Pulse Pod readers with an overview of Kazakhstan’s pulse industry and discusses the rise and recent fall of its pulse production, as well as what the future holds for Kazakhstan’s lentil, pea and chickpea exports.

Source: Atameken-Agro’s presentation at the Future of Pulses Conference, Kyiv, Ukraine, Nov. 29, 2019.

Kintal: I worked in the banking sector for 15 years and headed Astana Finance, one of Kazakhstan’s largest investment banks. In 2004, Atameken-Agro was founded, and I’ve been a co-owner from the start. In 2013, the shareholders appointed me as the company’s Chairman, and that’s when I really got involved with pulses.

Kintal: Atameken-Agro owns 300,000 hectares of land. When I became the company’s Chairman, we started out seeding 250,000 of the 300,000 hectares, and have been gradually increasing the seeded area year after year. This year, we plan to seed 290,000 hectares. As a result, crop production has increased as well, from 250,000 MT in 2013 to 500,000 MT in 2017 and 400,000 MT in 2018.

Over the past six years, we also significantly diversified our products. In 2013, the company focused mainly on grain production, such as wheat and barley. Now, we also produce oilseeds, including rapeseed and linseeds, and pulses, including lentils, chickpeas and peas. These additions were the result of the company’s adoption of no-till farming, which requires a continuous crop rotation. Hence, oilseeds and pulses now each occupy 25% of our seeded area.

Kintal: In Kazakhstan, we grow lentils, peas and chickpeas, all of which are well suited to the local climate. Given the country’s recent experience growing these pulses, we should be able to continue working with them and increasing production over time. The main challenges we face right now, though, include the decline in prices and market instability. For instance, in 2016, Kazakhstani producers greatly increased their lentil production in response to skyrocketing prices the year before. Now, however, prices are not nearly what they used to be. Farmers don’t see the benefit of continuing to grow lentils now that the return is not even enough to cover production costs. Part of the problem is that many farmers don’t have the proper hardware to work with pulses, and that prevents them from making the production process more efficient. Moreover, Kazakhstan lacks the seeds to produce the products currently in demand. The inadequate supply of quality seeds is another factor that keeps us from realizing the country’s full pulse production potential.

Kintal: Kazakhstan doesn’t consume a lot of pulses because they aren’t part of the local cuisine. That said, lentil and pea soups are gaining in popularity here, but not enough to show a noticeable change in local consumption. Most of the pulses we produce go to export markets.

Kintal: In terms of peas, Afghanistan has been the primary buyer for the past three seasons. Last year, 36% of Kazakhstan pea exports went to Afghanistan. Uzbekistan was second, with a 29% share, followed by Spain with a 17% share.

In terms of lentils, the vast majority go to Türkiye. Last year, Türkiye took 75% of Kazakhstan’s lentil exports, but that was down from 92% in 2017. Other countries, like Afghanistan and Iran, are now buying more Kazakhstani lentils.

Türkiye is also the major destination for Kazakhstani chickpea exports.

Kintal: Yes, the government is interested in diversifying agricultural production. However, most of its effort has been on oilseeds rather than pulses. This is because the government perceives oilseed markets as more stable and attractive than pulse markets.

Kintal: Climate and weather did play a significant role in reducing our lentil output last year. In the North Kazakhstan Region, the major lentil growing area, the harvest was disrupted by heavy rains and a considerable share of the crop had to be abandoned in the fields. On top of that, fewer hectares were seeded to lentils to begin with because of declining prices and high production costs.

Until market conditions improve, I think we’ll continue to see pulse production decline in Kazakhstan. Regionally, Russia is our biggest competitor because of its maritime access (Kazakhstan is landlocked) and better weather conditions in some regions. But I think, despite these disadvantages, Kazakhstan is capable of competing both in terms of quality and quantity.

The way I see it, local farmers still see promise in the pulse sector and I expect Kazakhstan will continue producing pulses. In time, I see the pulse sector here establishing a stable and reliable position in the market.

Source: Atameken-Agro

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.