March 7, 2023

Carla Borges, trade director of NG Trade (formerly Fazenda Nova Geração) in Brazil, discusses a continued downturn for mung beans, the resurgence of La Niña, and the implications of Brazil's new government.

The market scenario in 2022 was very challenging. We felt the world economy slow down combined with inflation both in the sourcing of grain from producers and in freight costs.

Of course, in Brazil the pulses and specialty grain are mostly produced in the second crop, after soybeans*. Last season Brazil had record prices for soybeans — 266% higher per ton than now — and that expectation transfers to the second harvest where pulses are grown. The result was very high prices to source sesame seed and beans, high costs for road and ocean freight and weak demand for those particular crops. The exporter often either broke even or lost money, especially those who agreed early contracts.

The slowness to resell products due to lower demand and international inflationary crisis badly impacted the exporter. We at Fazenda Nova Geração, as producers and exporters, adapted to this reality by focusing on the financial calculations — whether it was better to export or sell in the internal market. The company’s financial health is most important for us.

*Generally between early January to mid-March

We saw price inflation for soybeans and corn, which drove inflation of everything else — fuel, machinery, et cetera. For example, we would buy a combine harvester two years ago for 1.5 million reais (Approx. USD 288,689) and now they can cost 4 million reais (Approx. USD 769,837). As a result the farmer hopes to sell his crops for double the price, or at least 50% higher, but we haven't seen returns like that for pulse crops like mung beans.

Two years ago we were selling mung beans for $900/950 per ton, and last year we sold for $700/790 maximum, with very low demand because other countries like India and Pakistan suffered from inflation and currency devaluation. We had a big problem selling to Pakistan as they didn't have sufficient US dollars to pay us.

The result is that it doesn't match with the Brazilian reality. Here, farmers expect the same to happen with pulses as what happens with soybeans and corn – i.e. that their price would double – but the opposite happened. They didn't have any incentive to seed beans anymore, especially the cheap beans, like brown eye and mung.

Rises for agricultural equipment have had a serious financial impact on farmers

I think it's because the countries that are consumers of mung have suffered with the exchange rate evaluation. Devaluation of the currency is good for us, but very bad for them as they have less purchasing power. This affected the demand a lot, and there was also good production internally, that's why I think India had some restrictions on importing to help regulate the price.

I used to seed around 2000 hectares of mung beans but this year I just sold everything and I'm not seeding any mung at all.

The threat I see to pulse acreage is competition from sorghum or corn substitutes used for animal feed, which can have a better payback than pulses. Everything always depends on soybeans — we're seeing a very late first harvest because it's rainy in Mato Grosso, which is delaying the harvest of corn and soybeans and therefore the seeding of the second corn crop. If the seeding window for corn becomes too short, we will have to find substitutes, and those substitutes will be beans or something for animal feed.

However, beans are not giving much return, so the producer thinks 'oh, I'm going to plant something that can substitute for animal feed’ — not necessarily sorghum, but something that could be for animal feed as anything you can substitute for corn will go up in price as the price of corn rises.

“Here, farmers expect the same to happen with pulses as what happens with soybeans and corn – i.e. that their price would double – but the opposite happened. They didn't have any incentive to seed beans anymore, especially the cheap beans, like brown eye and mung.”

In agriculture in general we see a slowdown of growth. Costs have increased a lot. PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores), Lula's party, has a tradition of exporting high interest rates and interfering more in the economy, not monitoring fiscal health. That produces either inflation or a high cost of borrowing. Brazilian farmers are highly dependent on financing, so they will be very careful to invest in production if money begins to cost too much. For specialty grain it’s a little different — low prices on the international market are discouraging production more than politics.

Many farmers are concerned about Lula’s government, but the main thing I’m concerned about regarding the new government is the possible taxing of exports — that could be very bad, and that could happen.

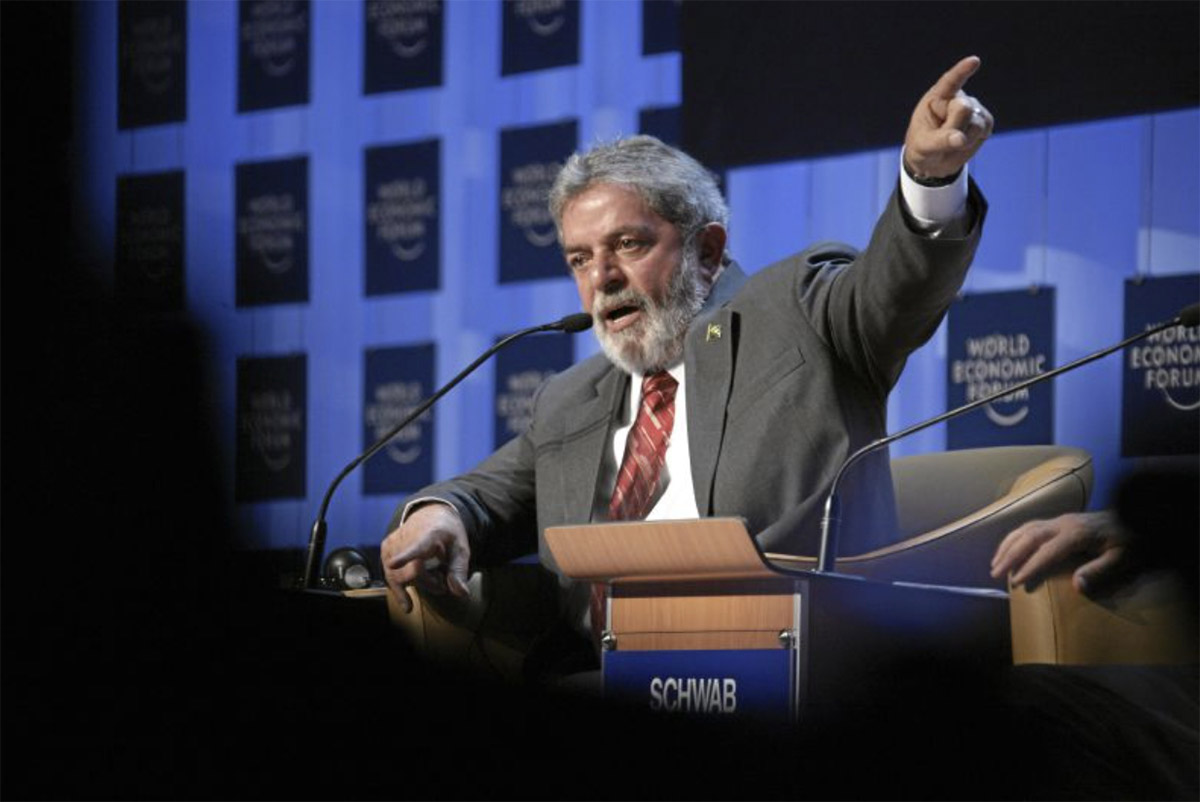

Brazil’s new president and leader of the Workers Party, Lula da Silva

It’s interesting, a slightly controversial topic in Brazil at the moment is the appearances of new farmland being cultivated that wasn't previously, land that is being used for growing soybeans. But a result of these new areas is that there will be other crops that need to be rotated in and, as pulses are usually lower cost crops, they can be a good option when the land isn't so old, or the farmer prefers not to invest in corn. They may see cow peas and other pulses as less of a risk.

That can mean a lot of acreage. For example, I live in Mato Grosso and five years ago there were no pulses and no sesame. Now we are producing a lot of them in Tocantins, Piaui — States that are bigger than some European countries!

So I think there is likely to be some compensation for pulses as the increase of acreage for agriculture grows. But it's never certain that the farmer who produces pulses this year will produce pulses next year – the only thing farmers are interested in is the outcome and profitability of their crops.

“Many farmers are concerned about Lula’s government, but the main thing I’m concerned about regarding the new government is the possible taxing of exports — that could be very bad, and that could happen.”

Some areas are experiencing very bad drought, especially in the south, down where it's affecting Argentina. For the first crop – especially pinto beans and black beans – it's bad, and will reduce production for sure.

We're also seeing very cold winters that affect the state of Mato Grosso do Sul and Goias. For the last two years we've faced issues with frost in June, so for the second crop that's also a potential risk.

We always have the seasons of higher prices during corn and soybeans harvests, which is a short window: March and April for soybeans and July and August for corn. The specialty grain trader knows it and often uses the windows of better freight prices.

In 2022, I couldn't export anything until December because freight costs were terrible – to export then would've meant me almost paying to work. Instead, I waited and saw the prices are coming down and now it's back to regular margins. But it was a big challenge. If it comes up again, it will be a struggle.

Freight prices and availability have returned towards pre-pandemic norms

It would certainly mean more production cost rises, which is always a bad thing both for producers and consumers. No doubt we would see inflationary pressure again also.

It’s back to normal. Prices shrank and we can have our margins back! It more than doubled our costs last year for this season which means our margins for this harvest are very tight, but for the next season we'll be back to normal.

Yes, Brazil can become self-sufficient in anything. There is a saying that we use a lot here: whatever Mato Grosso decides to plant, will mean a flood of the product in the market. That’s because of the immensity of arable areas we have available.

Yes, I’ve not been working with cowpeas for a little while, but a friend of mine who is producing in Mato Grosso says that the varieties we have available are turning brown. This doesn't seem to happen in the north-east.

Black eyed peas with a very white coloring are more accepted in both the internal market and the international market – any bean that turns darker depreciates in value. Obviously, farmers don't like to discount the product, so this can create a lack of interest in planting it, especially in a bearish market.

From the farmer's perspective it would be great to have more productive and disease resistant beans — it would reduce production costs and increase supply in the market.

Cowpeas in Mato Grosso are struggling to retain more desirable white colouring

Farmers are always confident, otherwise they wouldn’t invest thousands of dollars in land and pray for rain. But, we are much more cautious this year. We had very high production costs in 2022/2023 and our margins are very tight now. In addition to that, the cost of financing is way too high (around 17% APR in reais and 10% APR in US dollars), so leverage for investing is not an option at the moment. This is holding agriculture back from keeping the boost we saw in 2021/2022, when we had the opposite scenario.

We are also concerned about global demand, but Fazendas Nova Geração has been facing this up and down market for 40 years, so we prepare ourselves for bad times. In the end, we know that agriculture in Brazil will always prosper.